Volcanic glass has been discovered at more than 500 archaeological sites in western Canada. Geologically speaking, it shouldn’t be there.

Now, researchers may have answered how these artifacts made of obsidian ended up so far away from their point of origin, according to a March 14 study published by the Archaeological Survey of Alberta.

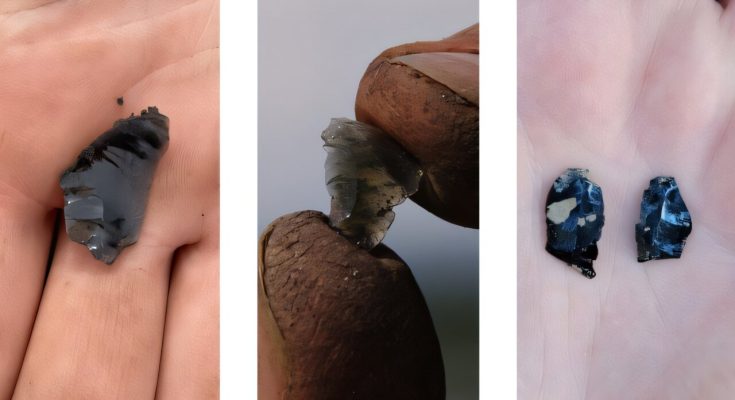

“Finding obsidian at an archaeological site is a bona fide indicator” of long-distance trade among prehistoric populations, study author and archaeologist Tim Allan said.

Obsidian was likely traded as part of the “complex and dynamic relationships connecting millions of Indigenous North Americans,” Allan said.

One of the sites where obsidian was found—GbQn-13—is about 7,000 years old.

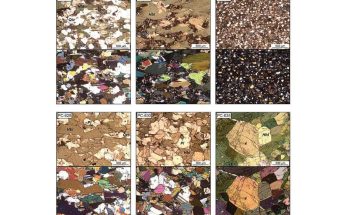

Using X-ray fluorescence technology, Allan traced 383 obsidian artifacts from 96 sites across Alberta to their geological source and revealed they came primarily from four sources: Bear Gulch in Idaho, Obsidian Cliff in Wyoming, and Anahim Peak and Mount Edziza in British Columbia.

Some of the obsidian artifacts, including arrowheads and spear tips, traveled nearly 750 miles from their source, according to Allan.

“A single piece of obsidian likely exchanged hands many times,” he said.

According to the study, a large portion of the obsidian deposits were uncovered at bison jumps—areas where indigenous hunters lured bison off cliffs to fall to their deaths.

Allan suggests the distribution of obsidian at these sites may be related to communal bison hunting practices, but additional research is needed.

River networks likely also played a role in prehistoric trade and obsidian distribution, according to the study.

“Indigenous communities were extremely interconnected prior to European contact and colonization,” Allan said.

“These trade networks spanned thousands of kilometers, we are only scratching the surface of how complex relationships between different groups were,” Allan told McClatchy News.

Allan’s research is part of the Alberta Obsidian Project.