Earth formed about 4.6 billion years ago, during the geological eon known as the Hadean. The name “Hadean” comes from the Greek god of the underworld, reflecting the extreme heat that likely characterized the planet at the time.

By 4.35 billion years ago, Earth might have cooled down enough for the first crust to form and life to emerge.

However, very little is known about this early chapter in Earth’s history, as rocks and minerals from that time are extremely rare. This lack of preserved geological records makes it difficult to reconstruct what Earth looked like during the Hadean Eon, leaving many questions about its earliest evolution unanswered.

We are part of a research team that has confirmed the oldest known rocks on Earth are located in northern Québec. Dating back more than four billion years, these rocks provide a rare and invaluable glimpse into the origins of our planet.

Remains from the Hadean Eon

The Hadean Eon is the first period in the geological timescale, spanning from Earth’s formation 4.6 billion years ago and ending around 4.03 billion years ago.

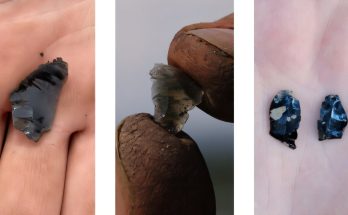

The oldest terrestrial materials ever dated by scientists are extremely rare zircon minerals that were discovered in western Australia. These zircons were formed as early as 4.4 billion years ago, and while their host rock eroded away, the durability of zircons allowed them to be preserved for a long time.

Studies of these zircon minerals have given us clues about the Hadean environment, and the formation and evolution of Earth’s oldest crust. The zircons’ chemistry suggests that they formed in magmas produced by the melting of sediments deposited at the bottom of an ancient ocean. This suggests that the zircons are evidence that the Hadean Eon cooled rapidly, and liquid water oceans were formed early on.

Other research on the Hadean zircons suggests that Earth’s earliest crust was mafic (rich in magnesium and iron). Until recently, however, the existence of that crust remained to be confirmed.

In 2008, a study led by one of us—associate professor Jonathan O’Neil (then a McGill University doctoral student)—proposed that rocks of this ancient crust had been preserved in northern Québec and were the only known vestige of the Hadean.

‘Big, old solid rock’

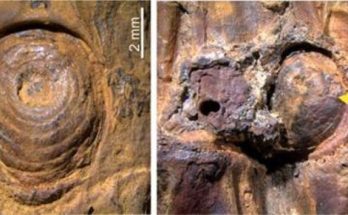

The Nuvvuagittuq Greenstone Belt is located in the northernmost region of Québec, in the Nunavik region above the 55th parallel. Most of the rocks there are metamorphosed volcanic rocks, rich in magnesium and iron. The most common rocks in the belt are called the Ujaraaluk rocks, meaning “big old solid rock” in Inuktitut.

The age of 4.3 billion years was proposed after variations in neodymium-142 were detected, an isotope produced exclusively during the Hadean through the radioactive decay of samarium-146. The relationship between samarium and neodymium isotope abundances had been previously used to date meteorites and lunar rocks, but before 2008 had never been applied to Earth rocks.

This interpretation, however, was challenged by several research groups, some of whom studied zircons within the belt and proposed a younger age of at most 3.78 billion years, placing the rocks in the Archean Eon instead.

Confirming the Hadean Age

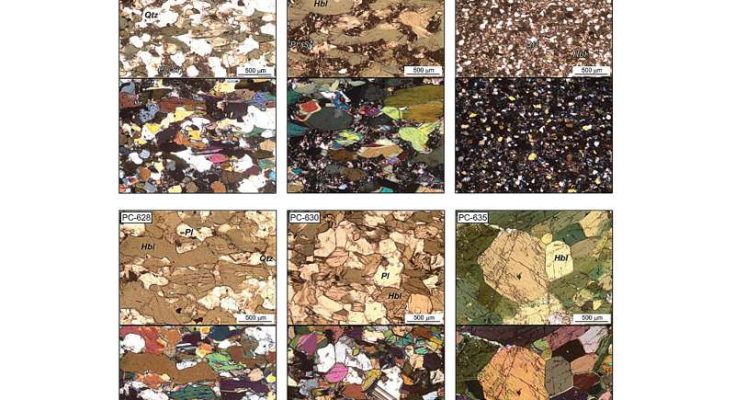

In the summer of 2017, we returned to the Nuvvuagittuq belt to take a closer look at the ancient rocks. This time, we collected intrusive rocks—called metagabbros—that cut across the Ujaraaluk rock formation, hoping to obtain independent age constraints. The fact that these newly studied metagabbros are in intrusion in the Ujaraaluk rocks implies that the latter must be older.

The project was led by master’s student Chris Sole at the University of Ottawa, who joined us in the field. Back in the laboratory, we collaborated with French geochronologist Jean-Louis Paquette. Additionally, two undergraduate students—David Benn (University of Ottawa) and Joeli Plakholm (Carleton University) participated to the project.

We combined our field observations with petrology, geochemistry, geochronology and applied two independent samarium-neodymium age dating methods, dating techniques used to assess the absolute ages of magmatic rocks, before they became metamorphic rocks. Both assessments yielded the same result: the intrusive rocks are 4.16 billion years old.

The oldest rocks

Since these metagabbros cut across the Ujaraaluk formation, the Ujaraaluk rocks must be even older, placing them firmly in the Hadean Eon.

Studying the Nuvvuagittuq rocks, the only preserved rocks from the Hadean, provides a unique opportunity to learn about the earliest history of our planet. They can help us understand how the first continents formed, and how and when Earth’s environment evolved to become habitable.

Journal information: Science

Provided by The Conversation