#Abala Bose # Saptarshi Mallick # An Author’s Afternoon # Prabha Khaitan Foundation # Travelogues # Feminism

IBNS-CMEDIA: Author Saptarshi Mallick, an Assistant Professor at the Department of American Studies (Research Area for American Literary and Cultural History with a Focus on (Trans-) Nationality and Space), University of Graz, Austria, was the guest at An Author’s Afternoon hosted by Prabha Khaitan Foundation at Taj Bengal, Kolkata on August 22. The author of Connecting Spaces – The Travelogues and Letters of Lady Abala Bose, Prof. Mallick spoke on the pioneering social reformer, educationist, and philanthropist in colonial Bengal in conversation with Kaberi Chatterjee. IBNS correspondent Souvik Ghosh brings excerpts of the conversation…

Photograph of w:Abala Bose from The Life and Work of Sir Jagadish C. Bose (1920) by Patrick Geddes. Photo: Wikipedia Creative Commons

Photograph of w:Abala Bose from The Life and Work of Sir Jagadish C. Bose (1920) by Patrick Geddes. Photo: Wikipedia Creative Commons

Q. How did it all begin for you?

A. After completing my PhD on Baptist Missionaries from the University of Calcutta, I was in search of something new because I have always been deeply fascinated by archives—Bangiya Sahitya Parishad, Asiatic Society, Goethals Library at St. Xavier’s College, the “minus one floor” of the National Library with its distinct smell that energises me, and more recently, the Angus Library and Archive at Regent’s Park College, University of Oxford, where I have free access.

Sister Nivedita, Sister Christine, Charlotte Sevier, and Lady Abala Bose in Mayavati. Photo: Wikipedia Creative Commons

Sister Nivedita, Sister Christine, Charlotte Sevier, and Lady Abala Bose in Mayavati. Photo: Wikipedia Creative Commons

Q. What drew your attention to Lady Abala Bose?

A. It all began with Professor Bashabi Fraser, CBE and Director of the Scottish Centre of Tagore Studies. With her, I made my first visit to Acharya Bhavan. While exploring the museum, I came across a file containing some documents. I soon discovered they were travelogues—later published in this book. I consulted Professor Parul Chakrabarti, Director of Acharya Bhavan, and Professor Fraser, who encouraged me to pursue this as my post-doctoral research.

I found that Lady Abala Bose wrote 13 travelogues—12 published in Mukund and one in Prabashi. There was also correspondence with Rabindranath Tagore referenced in the manuscript, which we later digitised and preserved at Acharya Bhavan.

During this research, I connected with late Professor Tapati Gupta, who introduced me to Professor Stephan Brandt at Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz, Austria, where I pursued my post-doc. While the university department focused on transnational travel writing, I explored Lady Abala Bose’s travel writings—an area less known compared to her work with the Nari Siksha Samiti and women’s education. Her writings on India and abroad became the foundation of this project.

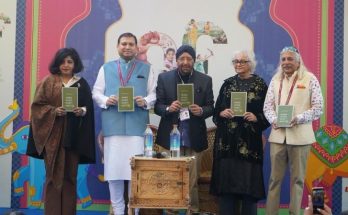

Esha Banerjee felicitating Guest Author Saptarshi Mallick. Photo: PKF

Esha Banerjee felicitating Guest Author Saptarshi Mallick. Photo: PKF

Q. Tell us how Lady Abala Bose managed to break through the glass ceilings in colonial Bengal.

A. She was deeply devoted to her husband but also drew inspiration from Sister Nivedita and Rabindranath Tagore. Her memoirs are simple yet reflect pragmatism, cultural enrichment, and a deep humanism in the context of broader struggles for liberation. Through her travelogues, she created “contact zones” that presented history and culture not as separate entities but through interaction, co-presence, and shared practices. This synthesis is crucial for shaping a cosmopolitan perspective in travel writing.

From her descriptions, I observed she avoided an autobiographical focus. Instead, she keenly documented people’s lifestyles, education, discipline, and food habits without adopting the coloniser’s gaze. She acknowledged the positive traits of the English but also critiqued their orientalist denigration and economic exploitation in India, highlighting the need for a free nation-state.

By interrogating anti-conquest narratives, she emerged as a “feeling individual”—a concept aligned with Rabindranath’s vision. This sensibility embraces diversity and cultural paradigms, enabling confrontation with “otherness” in ways that highlight both commonalities and differences, echoing Anthony Appiah’s notion of coexistence.

Vote of Thanks by Esha Dutta, Honarary Convenor NE Affairs and Ehsaas Woman of Kolkata. Photo: PKF

Vote of Thanks by Esha Dutta, Honarary Convenor NE Affairs and Ehsaas Woman of Kolkata. Photo: PKF

Q. Japan was very close to Abala Bose. What did she say about the country, especially in contrast to India’s purdah system?

A. She observed that in Japan, it was entirely a woman’s choice whether to meet or interact with a male visitor, even over something as simple as tea. This autonomy contrasted sharply with India’s purdah system at the time. She highlighted this cultural difference in her travelogue.

Q. Abala Bose also visited the US, known for its liberalism compared to the East. What was her response?

A. She cautioned against the excesses of extreme liberalism, particularly its effects on school-going children, and stressed the importance of parental guidance. At the same time, she admired the collective spirit in American households, where everyone contributed to chores—cooking, cleaning, washing.

She felt India should instill a similar spirit in children from an early age so that family responsibilities are shared equally by men and women. She emphasised that education in India should be structured to encourage this balance, rather than burdening women alone.

Welcome Note by Shefali Rawat Agarwal, Ehsaas Woman of Kolkata. Photo: PKF

Welcome Note by Shefali Rawat Agarwal, Ehsaas Woman of Kolkata. Photo: PKF

Q. You mention that Abala Bose believed women should be educated not merely to be good wives or mothers but because they have minds to be fulfilled. We often overlook Abala Bose, the feminist. She also founded schools. Are any of them still flourishing?

A. Yes, Vidyasagar Bani Bhawan is thriving. I visited the school and spoke with the principal. They have incorporated a compulsory course for students to learn about Lady Abala Bose, Rabindranath Tagore, and J.C. Bose. Despite the pressure of the syllabus, this course ensures her legacy in women’s education is remembered. Interestingly, however, the school community was unaware of her travelogues.

Q. How would you describe women’s travel writing in the 19th century?

A. Women writers of that era often had distinct, individual voices. Their accounts are rich in detail and resist the tendency of male travelogues to exoticise the unfamiliar. Instead, women emphasised cultural associations—food, local traditions, daily life—and grounded their observations in context.

This body of writing contributes significantly to a new genre of postcolonial literature. Like Abala Bose, many writers navigated a complex space—sometimes adopting colonial perspectives while simultaneously critiquing them. This ambivalence is characteristic of much of 19th-century Bengal’s intellectual landscape. Recently, I have extended my research to figures like William Carey in this context.

About the event

The evening commenced with a welcome address by Shefali Rawat Agarwal, Ehsaas Woman of Kolkata. The discussion, centered on Lady Abala Bose, was marked by insightful exchanges and drew active participation from the audience during an interactive Q&A session, making it a memorable experience for the city’s literary community.

The event concluded with a vote of thanks delivered by Esha Dutta, Honorary Convenor of North-East Affairs of the Foundation and Ehsaas Woman of Kolkata. As a gesture of appreciation, Esha Banerjee felicitated both the author and the conversationalist with Dokra handicrafts.

The evening ended with Saptarshi Mallick signing copies of his books for the guests, leaving behind cherished memories of words and ideas.