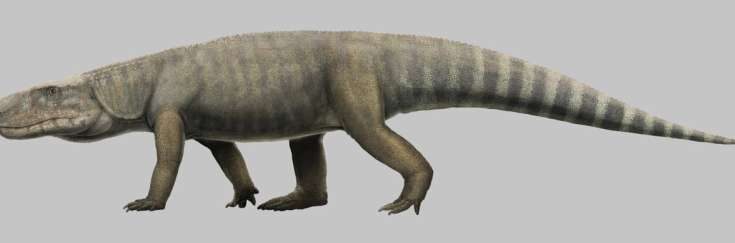

Life reconstruction of Mambawakale ruhuhu by Gabriel Ugueto, who retains the copyright. Only the skull, mandible, and a few postcranial elements are known for Mambawakale ruhuhu, so the rest of the body, tail, and limbs are reconstructed based on the anatomy of hypothesized close relatives of similar size. Credit: Gabriel Ugueto

#Fossils; #CrocodileEvolution; #Paleontology, #Geology;

A set of Triassic archosaur fossils, excavated in the 1960s in Tanzania, have been formally recognized as a distinct species, representing one of the earliest-known members of the crocodile evolutionary lineage, University of Birmingham research reported.

Researchers at the University of Birmingham, the Natural History Museum, and Virginia Tech University have named the animal Mambawakale ruhuhu. It is among the last to be studied of a collection of fossils dug up nearly 60 years ago from the Manda Beds, a geological formation in southern Tanzania.

The remains, which are the only known example of Mambawakale ruhuhu, include a partial skull, lower jaw, several vertebrae, and a hand. From there, the research team was able to identify several distinctive features that set it apart from other archosaurs found in the Manda Beds.

These included a large skull, more than 75 cm in length, and a particularly large nostril, as well as a notably narrow lower jaw and strong variation in the sizes of the teeth at the front of the upper jaws.

Richard Butler, Professor of Palaeobiology at the University of Birmingham says: “Mambawakale ruhuhu would have been a large and terrifying predator, which roamed across Tanzania some 240 million years ago. At around 5 meters long, it’s one of the largest predators that we know of from this period.

“Our analysis identifies Mambawakale as one of the oldest known archosaurs and an early member of the lineage that eventually evolved into modern crocodilians. It’s an exciting discovery because identifying this animal helps us to understand the rapid early diversification of archosaurs and enables us to add a further link to the evolutionary story of modern-day crocodiles.”

The study, published in Royal Society Open Science, also ties up the final loose end of an ambitious fossil expedition, undertaken by scientists including the paleontologist Alan Charig in 1963. Although most of the finds brought back from that expedition have now been formally described and cataloged, Mambawakale ruhuhu has remained unpublished until now.

In naming the specimen, the research team sought to recognize the previously little-acknowledged contributions of Tanzanians to the success of the 1963 expedition. The name chosen derives from Kiswahili, one of the native languages of Tanzania. Mambawakale means ancient crocodile, and ruhuhu refers to the Ruhuhu Basin, the region within which the fossil was excavated.