Several species of tiny fungi completely new to science—and all from Alberta—have been discovered through University of Alberta research.

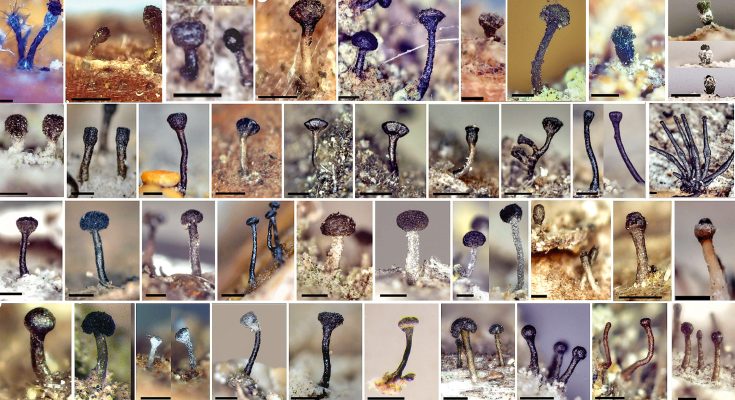

Three new evolutionary groups and 13 new species of “stubble fungi”—so named because they resemble beard whiskers—have been identified and described through a 13-year study, which also reported an additional 29 species found in the province for the first time, including nine in Edmonton.

The findings bring the total number of what are known as calicioids to 73 in Alberta, and “show the undiscovered biodiversity we have right in our own backyard,” says lichen scientist Diane Haughland, a lecturer in the Faculty of Agricultural, Life & Environmental Sciences who led the study now published in The Bryologist.

Found in areas ranging from a dog park in Edmonton’s river valley and a southern Alberta farmyard to wetlands and foothills forests, the wee, pin-like fungi with large heads grow on shrubs like wild rose bushes and carragana hedges, on dead wood and on native Alberta trees such as alder, poplar and spruce.

The presence of the new species signals hidden richness across the province’s Parkland Natural Region, which is often heavily altered by development for urban and agricultural uses, she adds. One of the discoveries, for example, marks the first time stubble fungi were found on wild rose bushes growing on agricultural land.

“Alberta is home to 13 new species that have not been found anywhere else on the planet, including a few in our own urban backyard. And while we tend to be blinkered and think our cities and parklands are not very interesting, they harbor exciting diversity that we don’t necessarily understand or appreciate yet. It makes me wonder about the unique conditions that are allowing these species to live here.”

Beyond Alberta, the foundational research also adds extensively to the taxonomic record for calicioids across North America. Four species of stubble fungi reported were new to all of Canada, one species was reported for the first time in western North America, and the research also documented new species in the Yukon and Northwest Territories.

The discoveries can help give a better snapshot of biodiversity by serving as a type of indicator for preservation efforts, Haughland notes.

“Functionally, many calicioids tend to occur in environments like old forests that have a lot of value from a conservation perspective. If we know that the fungi are more abundant in those habitats, that suggests these areas should be a priority for conservation.”

A collaboration with the Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute (ABMI), the study drew on a wide combination of surveys, research studies, monitoring programs and the institute’s field collections to locate and identify new species.

The research provides a database of about 3,500 records, including detailed descriptions, high-quality photographs, distribution maps and identification keys for 95% of the newly discovered species, serving as a comprehensive guide that helps fill a knowledge gap about North American calicioids.

It also allows other scientists, environmental consultants and even hobbyists to more easily find, identify and ultimately protect the fungi, Haughland notes.

“Knowing what species exist and where they live is the first step toward effective environmental monitoring and conservation. This resource is going to be helpful here, and around the world, for people to better understand both the existing and new species of stubble fungi. And while it’s neat to think about those 13 new species as unique to Alberta, that also makes them vulnerable. I hope this resource will help other scientists look for these species in their own backyards.”

Though tiny, calicioids have giant appeal, she adds.

“As scientists, we just love these things. Many are colorful, and they are often found in interesting places that are fun to explore. There is a treasure hunt aspect—you need to learn how and where to look for them, and the reward feels like finding a mini pot of gold sometimes,” Haughland adds.

“Maybe they also appeal to the same side of humanity that enjoys miniature cars or dollhouse furniture. They’re just darned cute!”

Provided by University of Alberta