The Sikait Project research team, directed by Professor Joan Oller Guzmán from the Department of Antiquity and Middle Age Studies at the UAB, recently published in the American Journal of Archaeology the results obtained from the January 2019 excavation season at the ancient seaport of Berenike, located in Egypt’s Eastern desert.

The paper describes the archaeological dig of a religious complex from the Late Roman Period (4th to 6th centuries CE) named the Falcon Shrine by researchers and located within the Northern Complex, one of the most important buildings of the city of Berenike at that time.

The site, which was excavated by the Polish Center of Mediterranean Archaeology and the University of Delaware, was a Red Sea harbor founded by Ptolomy II Philadelphus (3rd century BCE) and continued to operate into the Roman and Byzantine periods when it was turned into the main point of entrance for commerce coming from Cape Horn, Arabia and India.

Within this chronological period, one of the phases yielding the newest discoveries was the one corresponding to the Late Roman Period, from the fourth to sixth centuries CE, a period in which the city seemed to be partially occupied and controlled by the Blemmyes, a nomadic group of people from the Nubian region who at that moment were expanding their domains throughout the greater part of Egypt’s Eastern desert.

In this sense, the Northern Complex is fundamental in providing clear evidence of a link with the Blemmyes people, thanks to the discover of inscriptions to some of their kings or the aforementioned Falcon Shrine.

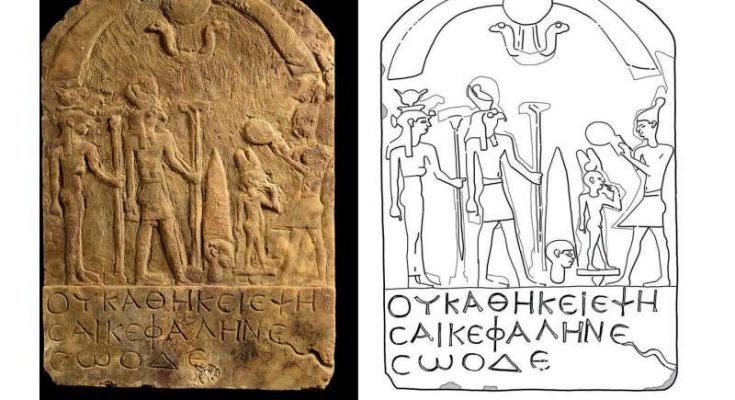

Researchers were able to identify a small traditional Egyptian temple, which after the 4th century was adapted by the Blemmyes to their own belief system. “The material findings are particularly remarkable and include offerings such as harpoons, cube-shaped statues, and a stele with indications related to religious activities, which was chosen for the cover of the journal’s current issue,” says UAB researcher Joan Oller.

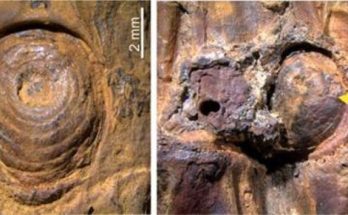

The most remarkable consecrated element found was the arrangement of up to 15 falcons within the shrine, most of them headless. Although burials of falcons for religious purposes had already been observed in the Nile Valley, as had the worshiping of individual birds of this species, this is the first time researchers discovered falcons buried within a temple, and accompanied by eggs, something completely unprecedented.

In other sites, researchers had found mummified headless falcons, but always only individual specimens, never in groups as in the case of Berenike. The stele contains a curious inscription, reading, “It is improper to boil a head in here,” which, far from being a dedication or sign of gratitude as normally corresponds to an inscription, is a message forbidding all those who enter from boiling the heads of the animals inside the temple, considered to be a profane activity.

Joan Oller says that “all of these elements point to intense ritual activities combining Egyptian traditions with contributions from the Blemmyes, sustained by a theological base possibly related to the worshiping of the god Khonsu.” He goes on to say that “the discoveries expand our knowledge of these semi-nomad people, the Blemmyes, living in the Eastern desert during the decline of the Roman Empire.”

#ShrineDiscovery; #EgyptianTemple