On a winter day in Northern Canada, the cold feels absolute. Snow squeaks underfoot and rivers lie silent beneath thick ice. Yet beneath that familiar surface, the ground is quietly accumulating heat.

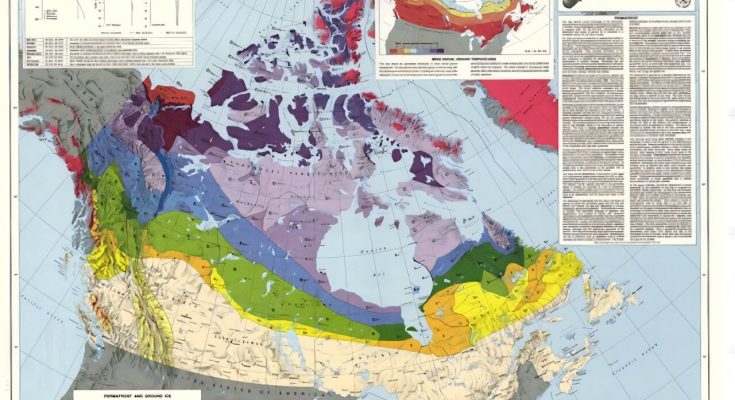

That hidden warming is destabilizing the frozen foundation on which northern communities depend. Permafrost—the permanently frozen ground that supports homes, roads, airports and fuel tanks across much of Northern Canada—is warming as a result of climate change. The North has warmed roughly three times faster than the global average, a well-documented effect of Arctic amplification—the process causing the Arctic to warm much faster than the global average.

Permafrost does not fail suddenly. Instead, it responds slowly and cumulatively, storing the heat of warm summers year after year. Over time, that heat resurfaces in visible ways: tilted buildings, cracked foundations, slumping roads and buckling runways. Long-term borehole measurements across Northern

Canada confirm that permafrost temperatures continue to rise even in places where the ground surface still refreezes each winter.

Communities in the Northwest Territories, Nunavut and the Yukon are already living with these consequences. As permafrost degrades, it undermines housing and transportation corridors and disrupts mobility and land-based activities. The impacts are uneven, with Indigenous communities often facing the greatest exposure and paying the highest costs.

A damaged access road or unstable fuel tank is not just an engineering inconvenience; it can interrupt supply chains, emergency access and daily life. What these patterns reveal is that permafrost thaw is not simply a surface problem. It’s the result of long-term, uneven warming below ground that reshapes soils, water, ice and infrastructure together, often accelerating damage well after climate warming begins.

Summer warmth penetrates deeper into the ground than winter cold can fully remove. Snow further reshapes this balance by insulating the ground, especially as a warmer, more moisture-laden atmosphere delivers heavier snow in cold regions, earlier autumn cover, longer spring persistence and uneven accumulation around infrastructure, all of which limit winter heat loss.

Buildings, foundations and buried infrastructure add their own steady sources of warmth. Each input may seem modest on its own. Over decades, their combined effect becomes decisive.

For much of the past century, northern engineering has been designed to keep heat out of frozen ground. Practices such as elevating structures on piles, minimizing ground disturbance and installing passive cooling systems like thermosyphons have proven effective under historically cold conditions. But these approaches depend on long, reliably cold winters. As winters shorten and insulating snow arrives earlier, the benefits of those practices are becoming harder to sustain.

From blocking heat to managing it

Engineers in Canada have already demonstrated ways to deliberately influence subsurface temperatures. Along northern highways and embankments, ventilated shoulders and air-convection systems have been used to increase winter heat loss from permafrost foundations, measurably cooling the ground beneath key infrastructure. These projects show that underground temperatures can be deliberately managed, not just endured.

More recently, work in the Yukon has shown that sloped thermosyphons installed beneath highway embankments can

lower permafrost temperatures and raise the permafrost table, stabilizing ice-rich ground that would otherwise continue to settle. These systems are effective but only as long as winters remain cold enough to drive heat extraction.

Geothermal engineering offers a more adaptable approach. In southern Canada and elsewhere, some buildings already use foundation piles that serve two purposes: structural support and heat exchange. Rather than allowing waste heat to leak passively into surrounding soil, these systems circulate fluid to move heat in or out of the ground as conditions require.

In northern permafrost regions, the same principle could be applied differently. Instead of allowing heat from buildings, pipelines or power systems to migrate downward into thaw-sensitive soils, foundation piles could intercept some of that energy and return it to buildings during winter, when heat demand is highest. In summer, operation would focus on limiting new heat input, preserving seasonal cooling gains.

This is not about turning permafrost into an energy resource. It is about preventing uncontrolled heat leakage, sustaining the very foundations that hold northern infrastructure in place.

Protecting what holds communities together

The implications extend far beyond individual buildings. Roads, airstrips, fuel storage facilities, water treatment plants, power lines and communication systems across Northern Canada all depend on stable ground. Many also introduce persistent sources of warmth through traffic, buried utilities and electrical infrastructure.

As thaw progresses, roads deform, fuel tanks shift and runways become unsafe. A settling airport runway, for example, can ground flights that deliver food, fuel and medical supplies for weeks at a time.

For infrastructure expected to remain in service for 50 years or more, managing subsurface temperature may matter as much as structural design itself. When these systems fail, the effects ripple outward, increasing isolation, raising costs and limiting access to essential services.

Indigenous partnership is essential

The impacts of permafrost thaw are not shared equally. Indigenous communities are often the most exposed, facing disproportionate damage to housing and infrastructure that underpins mobility, food security and access to health and education services.

Many northern communities also remain heavily dependent on diesel for heat and electricity, locking in energy systems that add persistent heat to the ground and raise the long-term cost of maintaining infrastructure.

Any approach to geothermal or ground-temperature management must therefore be developed in genuine partnership with Indigenous governments and residents. Engineering solutions that stabilize the ground while reducing fuel dependence will only succeed if they align with local priorities and support long-term community self-determination.

None of this replaces the need to rapidly reduce gre

enhouse-gas emissions. No technology can preserve all permafrost under unchecked warming. But in Northern Canada, adaptation is no longer optional.

Research shows that long before damage becomes visible, heat accumulates underground, weakening soils and reshaping landscapes. This is where infrastructure can play a central role, by influencing how heat enters, moves throughout and leaves the ground.

Canada now faces a choice: it can continue building as if frozen ground were static, or it can design for permafrost as what it is: a sensitive thermal system with a long memory. The heat accumulated below ground over decades reflects past decisions. But how much heat we add next, and how carefully we manage it, is a choice.

Provided by The Conversation