#MahatmaGandhi, #Lenin, #Russia

IBNS-CMEDIA: This short talk was delivered at the celebration of the 155th Anniversary of MK Gandhi in Moscow on the 2nd of October 2024 by Dr. Sergei Dmitriyevich Serebriany of E.M. Meletinsky Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities, Russian State University for the Humanities.

Talking about Gandhi-ji here and now, on such an occasion and before such an audience, is both a great honour and a hard task, especially as I have not more than fifteen minutes at my disposal. So I apologise in advance for speaking in brief statements, not always being able to support my statements by facts and/or reasoning.

The name of Gandhi-ji is widely known in this country, as in the rest of the world. But, I dare say, beyond the name as such, very little is really known to most people in Russia about the person called Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, who was born in the city of Porbandar, British India, one hundred and fifty five years ago.

Much has been written about Gandhi ji in English and other European languages, but rather little has been written about him in Russian. The reasons are not difficult to see. Gandhi ji, his views and his actions, did not suitably fit into “Soviet” ideological schemes. Under Stalin, Gandhi ji was considered “a reactionary”, “an agent of British imperialism” and therefore not a proper subject of attention.

Under Khrushchev, he was “rehabilitated”, but still not taken too seriously by scholars. And in the “post-Soviet” time, there cropped up too many other problems and interests, so that Gandhi-ji has remained rather neglected.

By 2019, to mark the 150th anniversary of Gandhi ji, the Moscow publishing house “Molodaya gvardiya” wanted to bring out a book about him in the popular series “Lives of Remarkable People”, but no Russian author could be found to write such a book. So they published a little book, in translation, by a French author. And till today there are practically no books, in Russian, about Gandhi-ji, worth reading and written by Russian authors.

It is indeed difficult to write and speak about Gandhi-ji in Russian, because he belongs to a world, to a culture very different from ours. Words of our language very often prove inadequate for describing the circumstances of his life, the turns of his thought, the motives of his actions.

Let me try and make my task easier by comparing Gandhi-ji with an equally famous Russian contemporary of his, Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924). During the last hundred years, several books and quite a number of papers were published (mostly in English) titled “Lenin and Gandhi” or “Gandhi and Lenin” – and even one book, in Russian, titled “Tolstoy, Lenin, Gandhi” (Prague, 1930).

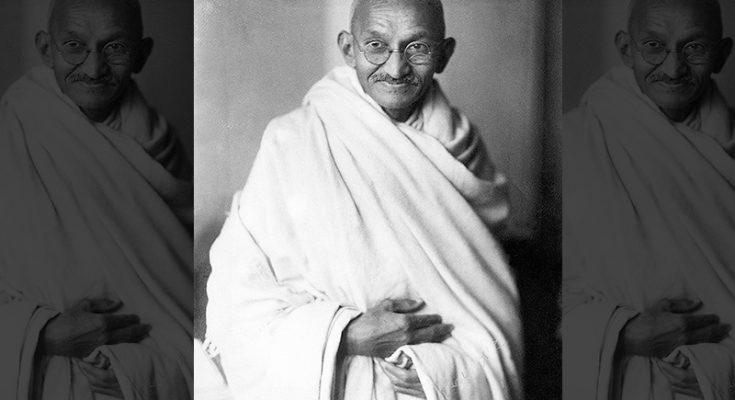

Photo courtesy: Wikipedia Creative Commons

Photo courtesy: Wikipedia Creative Commons

Gandhi and Lenin have been compared and contrasted in various ways. Indeed, there are both dissimilarities (obvious) and similarities (less obvious) between these two figures. To start with similarities, those two men were almost coevals. Gandhi ji (born on the 2nd of October 1869) was only about half a year older than Lenin (born on the 22nd of April 1870).

Next, they both have become legendary, almost mythical and, in a way, symbolic figures for their admirers and not only for them. These mythic and symbolic aspects have tended to eclipse and/or disfigure the real human dimensions of both personalities.

Thus, Gandhi ji is quoted as saying (or writing) that he was often regarded as a saint who strayed into politics, but actually he was a politician who endeavoured to be a saint. Indeed, Gandhi ji and Lenin were both shrewd politicians, the unquestionable leaders of their political parties.

Both have achieved their political goals: independence of India from the British crown, in the case of Gandhi, and a «socialist revolution» in Russia, in the case of Lenin. But, in both cases, the achievements happened to be mixed blessings: both politicians, by the very end of their lives, had to see that they got not exactly what they had wanted and striven for.

Gandhi-ji was shot dead, in 1948, by one of his political and ideological opponents. Lenin also, in 1918, got a bullet, which did not kill him on the spot, but, probably, contributed to his death in 1924.

As for dissimilarities, they are closely connected with the similarities. Both Gandhi ji and Lenin have become symbols – but of quite opposite values and ideals. Gandhi ji is a symbol of non-violence, of non-violent political actions. Lenin, on the contrary, is one of the symbols of revolutions by means of violence, of radical social and political changes effected through violence.

Lenin liked to quote a phrase of Karl Marx (1818–1883) from the first volume of the book «Das Kapital» (published in 1867): «Violence (force) is the midwife of every old society pregnant with a new one» (in the original German: «Die Gewalt ist der Geburtshelfer jeder alten Gesellschaft, die mit einer neuen schwanger geht»).

Another important dissimilarity between Gandhi ji and Lenin reflects the dissimilarity between the histories of our two countries. The history of India, like the history of Russia, has its share of cruelties, disasters and tragedies. But, on the whole, Indian history is more continuous and smooth than the history of Russia. Our history has been, especially during the last three-four centuries, a series of drastic changes, of radical breaks with the past.

The story of the anniversaries of Gandhi-ji and Lenin is a case in point. In 1969, the one hundredth anniversary of Gandhi-ji was widely celebrated in India as well as in the USSR.

In 1970 the similar anniversary of Lenin was widely celebrated in the USSR and, probably, in India as well. India keeps celebrating further anniversaries of Gandhi-ji, but I cannot even recall when we ceased celebrating further anniversaries of Lenin. In 1970 Lenin was hailed here as one of the greatest personalities in Russian and world history.

By today he has become a very controversial figure, even though there still are some people for whom he is a hero. After Russia’s painful experiences in the 20th century, hardly many Russians might be inspired by the ideas of violent social and political revolutions.

In India, Gandhi-ji has always had and still has critics and opponents, but, nevertheless, for most Indians, he remains a highly revered figure, “the Father of the nation”. Needless to say, Gandhi-ji is also respected and praised internationally. I am not sure that the same may be said now about Lenin. To close this topic, I think that a future Plutarch may write “Parallel Lives” of Gandhi-ji and Lenin. It might be a very interesting and instructive book.

The life of Gandhi-ji demonstrates both the continuity and discontinuity of Indian history. And it is only in the general context of Indian history that his life may be understood more or less adequately. Let me mention, in a nutshell, the most important points. The Indian (or South Asian) subcontinent is an area comparable in size and cultural diversity to Western and Central Europe.

In Europe, during what we call the modern age, roughly since 1500 AD, the dominant trend has been the development of the so called national states. In South Asia, on the contrary, it has been the time of imperial structures. Since the early 13th century, Muslims, coming through what is now Afghanistan from what we now call Central Asia, spread their power on the subcontinent.

At the beginning of the 16th century, Zahīr ud-Dīn Bābur (1483–1530), born in Andijan (now in Uzbekistan), a descendant of both Genghis Khan and Timur (Tamerlane), founded in Delhi the dynasty known as the Great Mughals, which, by the 18th century, united under its power almost the whole of the subcontinent. By that time, quite a sizable part of the local (subcontinental) population had converted to Islam.

The Empire of the Great Mughals formally existed till the middle of the 19th century, but already in the 18th century it started disintegrating. From the mid-18th till the mid-19th century, on its ruins, the enterprising British built their Indian Empire.

This new empire had rather a complicated structure (partly inherited from the Mughals). There were several provinces ruled straight by the British administrative structure, with the Viceroy in Delhi at the head, and several hundreds (!) so called native (or princely) states of various sizes, former vassals of the Mughals, which became a kind of vassals of the British Crown.

Gandhi-ji was born in one of the small native states (part of today’s Gujarat), in the family of the dewan of that state. Dewan (or divan) is a Persian word that may be translated as “first minister” or “prime minister” (Persian, let me remind you, had been the official language of the Mughal Empire).

As Gandhi ji wrote in his autobiography, at least two generations of his ancestors had been dewans in local native states. Most probably, his father wanted Gandhi-ji to keep the family tradition. But the British authorities adopted a law according to which those who aspired to become dewans had to be properly educated (Gandhi ji’s father had no formal education).

So, in 1888, 18 years old Gandhi-ji went to London to get educated in law (by that time he had learned enough English at school).

Two and a half years in London must have expanded the horizons of the son of a provincial dewan. When, in 1891, he came back home, he tried to work as a lawyer, but was not quite successful. In 1893 he got an offer that changed his life. By that time many Indians had moved to South Africa, part of the British Empire.

Gandhi ji was requested by an Indian Muslim businessman, who lived and worked in South Africa, to resolve his legal problems there. So, in 1893, 23 years old Gandhi ji went to South Africa and lived there 21 years, till 1914. At first he was just a successful lawyer, but soon he became what now would be called «a human rights activist».

He was requested by local Indians to defend their rights against discriminatory laws adopted by the local authorities. It was in the course of these activities that Gandhi-ji came to practice (from 1906–1907) what he first called “passive resistance” and later renamed as “satyâgraha”. It was in South Africa, in the 1890s, that Gandhi-ji read Lev Tolstoy’s book “The Kingdom of God is Within You”.

The ideal of non-violence, proclaimed in this book, impressed Gandhi-ji very much. It was also in the South African period of his life that Gandhi ji corresponded with Tolstoy, in 1909–1910. In those years Gandhi ji was not yet the politician he was to become later. He called himself a loyal subject of the British Empire which, as he believed, existed for the good of mankind. When he came back to India at the beginning of 1915, he supported the war efforts of the Empire against Germany.

It was only in 1919 that the course of events made Gandhi-ji change his mind. In 1920 he became the leader of the Indian National Congress and started his career as a politician fighting for the independence of India. It is sometimes said that Gandhi-ji, through his non-violent struggle, forced the British out of India. Fine as a heroic myth, it is obviously a misunderstanding.

The transfer of power, in 1947, from the British Crown to the leaders of the two newly independent states, India and Pakistan (actually to the leaders of the two parties: the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League) was a result of a whole complex of historical processes and events, Gandhi-ji’s non-violent politics being only one of those processes.

The bitter irony of history is that after that transfer of power, effected with the strict observance of legal norms, the subcontinent was engulfed in waves of violence, and Gandhi-ji himself, rightly called an apostle of non-violence, fell victim to an assassin. It may be said that, in the end, Gandhi ji personally, as a politician, has not been quite successful.

Nevertheless, I think, we may compare him to a hero of a classical tragedy who perishes in his struggle against the inimical fate and, in a way, triumphs in his very death.

George Orwell wrote in January 1949, one year after Gandhi-ji’s death: “…regarded simply as a politician, and compared with the other leading political figures of our time, how clean a smell he has managed to leave behind!”

Dr. Sergei Dmitriyevich Serebriany is the Director of E.M. Meletinsky Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities, Russian State University for the Humanities