President and CEO of the Canadian Olympic Committee David Shoemaker recently called for an additional $104 million in government funding for Olympic athletes.

He spoke about athletes “inspiring” Canadians to become participants in sport. And he warned that, without increased funding for Olympic athletes, there will be “dramatic reductions in participation in sport.”

Shoemaker follows a long line of athletes, sports leaders and politicians who have argued that the “inspiration” from successful athletic performances justifies the high levels of government funding for high-performance sport and hosting major international sports events.

Yet the evidence for such inspiration, also referred to by academics as the “trickle down” or “demonstration” effect, is at best wishful thinking.

At the Centre for Sport Policy Studies at the University of Toronto, we have been collecting data about the relationship between high-performance sport and sport participation for more than 20 years. We have found no evidence to support the claimed “inspiration” effect.

The evidence

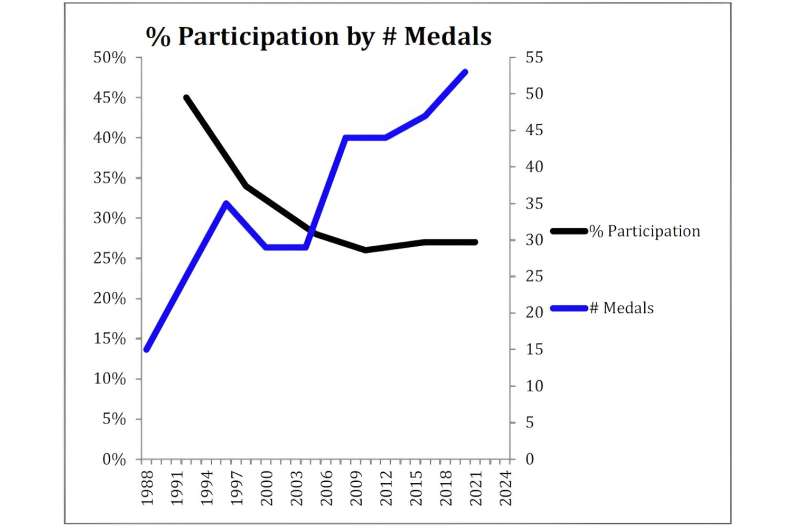

Our most recent report examines three key areas: the total number of medals won by Canadian athletes during each four-year Olympiad from the 1988 Calgary Olympics to the 2020 Tokyo Olympics; General Social Survey data on organized sport participation in Canada since 1992; and Sport Canada budgets, mostly allocated to high-performance sport, since 1988.

We found two clear trends: the more money the Canadian government spends on high performance sport, the more medals Canadian athletes win.

But at the same time, the more money the government spends and the more medals Canadian athletes win, the fewer Canadians participate in organized sport.

This has declined from a high of 44% in 1992 down to a plateau of approximately 27% since 2005.

Causality

The evidence, in Canada and internationally, supports a direct relationship between the amount governments spend on high-performance sport and the number of medals won by national team athletes.

Yet the relationship between federal government spending on sport and broadly-based participation is much more complex. Many other factors need to be taken into consideration. In Canada’s case, they include:

- An aging population with an expected decline in organized sport participation.

- Increasing immigration: new Canadians are less likely to participate in traditional organized sports because of various barriers.

- Cuts to education and other public sector budgets that previously supported opportunities to participate at less elite levels of sport.

- Too much focus on talent identification and early specialization in sport, which discourages children with slower growth or skill development from participating.

- The increasing cost of participating in organized sports (pay-for-play) making it unaffordable for many families and individuals.

- A shift, internationally, away from playing organized competitive sports toward more recreational participation.

Despite the complex causality, there is no evidence that the success of Canadian athletes results in increased sport participation in the general public.

Inspiration is not enough

We do not doubt that many young Canadians are inspired by the achievements of Canadian athletes; that’s not the issue. But only a few have the means or opportunity to realize their inspiration if they want to take up sports.

Inspiration doesn’t break down the barriers that prevent so many young people from participating in the first place. Family income, gender, sexuality, (dis)ability, geographical location and other factors can all, individually and in combination, have an enabling or a constraining effect on participation in organized sports.

It is lamentable that the Canadian sports system makes no concrete or intentional effort to enable increased grassroots participation. It is hypocritical to say inspiration will lead to sport participation without first providing young people with the means and opportunity to realize their “inspiration.”

It also is insensitive to threaten decreases in participation, or blame people for failing to be inspired, when nothing has been done to enable their participation.

To actually increase participation, an intentional, research-based, consultative, community-grounded, strategic investment in new opportunities will be necessary, including accessible facilities, qualified leaders, and the means for children, youth and adults to overcome the socio-economic barriers they face.

The Future of Sport Commission

Fortunately, there is a timely opportunity to raise these issues in the federal government’s recently announced Future of Sport Commission. The commission’s aim is to develop recommendations for improving safety in Canadian sport and for improving the Canadian sport system. It should address the fairness and sustainability concerns raised above and developed in our report.

It should make concrete—not simply rhetorical—recommendations for enabling more participation. And it should work to realize the ideals outlined in UNESCO’s International Charter on Physical Education, Physical Activity and Sport, which Canada helped initiate and to which it is a signatory.

In the charter, the opportunity to participate in physical education, sport and recreational physical activity is recognized as a right of citizenship. The widespread enjoyment of sport for all should also make the possibilities of achieving high-performance available to a far broader base of the population.

In addition, a sustainable high-performance sport system would end the culture of win-at-all-costs and recognize athletes as rights-bearing citizens whose safety, health and well-being, current and long-term, is more important than the immediate gratification of a medal.

Provided by The Conversation