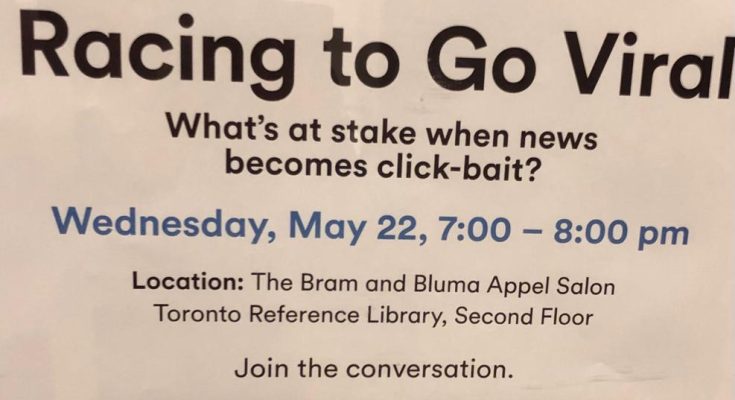

CMEDIA: Canadian Journalist Foundation (CJF), in collaboration with its long time partner Toronto Public Library (TPL)– an institution committed to fostering informed communities with reliable information – presented last week in Toronto Reference Library a discussion on journalism, media, and culture by two exceptional speakers Ben Smith and Elamin Abdel-Mahmoud and how it affects Canada.

Ben Smith, the founder of Traffic: Genius, Rivalry, and Delusion in the Billion-Dollar Race to Go Viral, the editor-in-chief of Semaphore and past editor-in-chief of BuzzFeed News, and Elamin Abdel-Mahmoud, a media personality, author, and broadcaster, a former culture writer at BuzzFeed News, the host of CBC Radio’s Daily Arts, pop culture, and entertainment show and a valued member of our CJF board of directors.

CJF extends thanks to its broadcast partner for this event The Cable Public Affairs Channel (CPAC), reportedly a Canadian specialty television channel owned by a consortium consisting of Rogers Communications, Vidéotron, Cogeco, Eastlink, and Access Communications.

Around the world, and here in Canada, the media landscape continues to grapple with seismic shifts brought about by the internet, social media, and now artificial intelligence. These changes have completely transformed how news is shared and consumed, and the rise and fall of viral news outlets has profoundly impacted news business models and influenced public trust and interaction with the media.

To help make sense of this past digital news decade and what comes next, Ben and Elamin present their conversation.

Elamin: I’ve been reading this oral history of ESPN which has access to a cable channel offered at a very low price and it is covering high school sports games in Connecticut. But 30 years later, when we look at ESPN and realize where we are.

There was a moment in the late 80s where you look at ESPN, and MTV, and CNN, who looked at cable and said, there’s a brand new type of pipe and begin to think that we can fill this pipe with some content to make some money. And 30 years later, we look at a different type of pipe, the social media pipe. We see Facebook, Twitter, we see all these other social media pipes. And a company like thinks of filling these pipe with content to make some money. What went wrong? Why was that the case?

Ben: I think that’s an incredibly astute question. It’s really, it’s the business of this whole thing. The people who laid the wires realized that if you were going to sign up for cable, you needed some good content. And they paid a lot of money to companies like ESPN and CNN for these huge businesses. And the people who built companies like BuzzFeed, like Vice, they didn’t familiarize themselves with that analogy. They were the same people. The people who made, the chairman of Vice was the founder of MTV. The chairman of BuzzFeed was also a guy who made most of his money on MTV.

It just didn’t work out that way. The idea that places like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube tried to compete with places like Netflix by having more professional content and paying for it rather than paying journalists and creators. I think there was this real Silicon Valley ideological hostility to the notion of professional media in any sense and journalism, and that is the reason among other things, why they never paid for anything.

Elamin: And the notion of journalism, the notion that like, why do these people on the East Coast get to decide what’s true? Why not let the crowd decide?

Ben: I think there was a real hostility to the idea of journalism, and then that whole ecosystem basically collapsed. But we believed that we would build entire business an amount of traffic into money. And 2015 was the year when it happened. it’s these companies in general, tech companies, like to talk about their values and like to talk about their missions. But what went wrong was the main concentration on the business and not on journalistic ideals.

Facebook as an entity wanted to be a part of creating a new news ecosystem. But that did not happen. There’s a certain reality to the idea that Facebook has built an entire business model out of looking and seeing what’s popular and then thinking of doing it better than other social media channels. But Twitter at that time was kind of an ascendant in 2011, 2012. And instead of being involved in news content, Facebook had at its core some democratic event.

But the companies which operate these high-growth, complicated businesses in these competitive environments, their mission statement doesn’t make any sense. And in fact, they’re looking over their shoulders all the time.

And then Barack Obama was the Facebook candidate because Facebook was, in 2008, a student organization. In 2011, Obama visited Facebook, and he didn’t have to admit that he was there because he was a Democratic Party operation. But that was obviously the case why he was there.

Next thing they discussed is about this era of the internet versus reporting.

Elamin: Why did you resist giving people a gratifying theory of why the social web died?

Ben: I guess I am a little resistant to these grand internet theories. In part there were a bunch of contingent decisions. Facebook and Twitter and YouTube had to say that that they were going to be hostile to journalism, and not going to ever pay for professional content.

And in fact, I think you can make the case that Facebook, and the blue Facebook app and Twitter would be healthier today if they had not thought of competing higher in the market. But I just think these weren’t inevitable. And there’s a sort of impulse to treat things as inevitable.

Elamin: Let me ask you about Jonah Peretti – an American internet entrepreneur, a co-founder and the CEO of BuzzFeed, a co-founder of The Huffington Post, and a developer of reblogging under the project “Reblog” — and Nick Denton. They are two different characters and with different philosophies. Do you want to talk about who they are?

Ben: I was part of this because there was also this moment in that period when the conventional wisdom was that Silicon Valley was dead. The internet popped. The internet, whatever, it’s over. And the real tech media innovation is happening in New York. And this was like an investment. Foursquare was the big company at that moment. Exactly. I was the mayor in New York. In that downtown scene, two of the people who were rivals and even a little bit enemies and acquaintances – I chose them because they had very different visions of the kind of cultural and political impact of the internet.

But also, ultimately to me, it’s interesting. It’s a story about culture and politics more than a story about business. And Peretti, kind of old-fashioned utopian believed that the internet was fundamental.

And this was a real opportunity for people on social media to be their best selves. On social media, you’re going to post like here’s a fundraiser for the victims of the earthquake. You’re going to try to present yourself. Well, Peretti didn’t know it was a fundraiser. This is what the psychology of it is. You would think that people would want their public selves to kind of be their best selves. And in the early social media – That’s not a crazy thought.

Elamin: The ability of the internet to allow people who feel so isolated to kind of see themselves, which also applies to Nazis, right?

Ben: Sorry. But in any case, Dan Savage had this totally different vision, which was that the internet would strip away the hypocrisy and the masks and the things that might unset in media because they were too rude or too anti-establishment or too destructive. And then the goal of the internet was going to be to say all the stuff that you hadn’t been allowed to say before for journalists. Sure.

And Gawker Media LLC – an American online media company and blog network founded by Nick Denton in October 2003 as Blogwire ,based in New York City – did do that. That was Gawker’s identity, his DNA. And specifically, to publish sex tapes.

Elamin: Why would you do that? I want to go back to the analogy you just made.

Ben: There’s a lot there. The idea that Dan Savage campaigned help queer kids see themselves, but we didn’t realize the idea that Nazis could also see themselves because in many ways that’s the media landscape that we find ourselves in now. Just Nazis looking at each other. Half the Internet is Nazis talking to each other. There is, I think an element of certain people who were present around the time who maybe didn’t see the thing they were learning.

There were these tools and ways of thinking about to get engagement. It gets retweets. But in any case, the thing to me that was the most interesting actually was that all these kinds of tools and ways of thinking that thought being witty. And obviously everybody was going to get online. It was going to reflect the politics of the whole society.

And specifically, the platforms had increasingly used this metric called engagement, which is to say that instead of showing you something because it’s in your network, that one of your friends posted it, or showing it to you because somebody liked it. They were looking for deeper signals that you were really engaged in this content, which would be commenting.

The tactic that predates the internet and isn’t about social media, but that plays incredibly well on Facebook. And we’re just obviously in this kind of populist moment when those things are rising to the surface. And social media is part of it. It’s sort of a declining trust institution but it is very challenging. The story that goes viral is the story that affirms that