IBNS: It has been three years since the demise of filmmaker Basu Chatterjee, who made ‘small’ things that constitute our life in the otherwise over-the-top world of Bollywood films look relatable, beautiful and gentle. The director also knew how to make those small little stories of his everyday characters successful on celluloid creating a niche for his middle-of-the-road cinema. Noted social worker and cultural patron Sundeep Bhutoria recalls the man on the third anniversary of his death (June 4, 2020)

The writer with Basu Chatterjee

The writer with Basu Chatterjee

By the end of the 1960s, Hindi cinema was poised for a change. The decade had largely been about escapist cinema, and though some of these had great songs, there was little that was creative and path-breaking by way of content. The odd exceptions – Bandini, Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam, Anupama and Teesri Kasam – only proved the rule about a decade that replaced the artistic aspirations of the 1950s with what has in effect come to define ‘Bollywood song-and-dance’ cinema.

The advent of the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) in 1962 played an important part in this change, with its first batches beginning to enter the industry, bringing in a change in aesthetics.

The year 1969 was to be a watershed in the history of Hindi cinema, with three films that proved instrumental in ushering in a new language, heralding the New Wave in Hindi cinema: Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome, Mani Kaul’s Uski Roti and Basu Chatterjee’s Sara Akash (all three were shot by K.K. Mahajan, who had graduated from the FTII in 1966, and who became synonymous with the New Wave and with the cinema of Basu Chatterjee).

Of these three film-makers, Mrinal Sen remained rooted largely to Bengali films and Mani Kaul carved a space for a personal cinema free of commercial considerations. It was Basu Chatterjee who, in conjunction with the films of Hrishikesh Mukherjee and Gulzar, provided an alternative to the big-budget extravaganza of mainstream films of the era (the Manmohan Desais and Prakash Mehras) and the spare aesthetics of arthouse cinema (driven by Shyam Benegal).

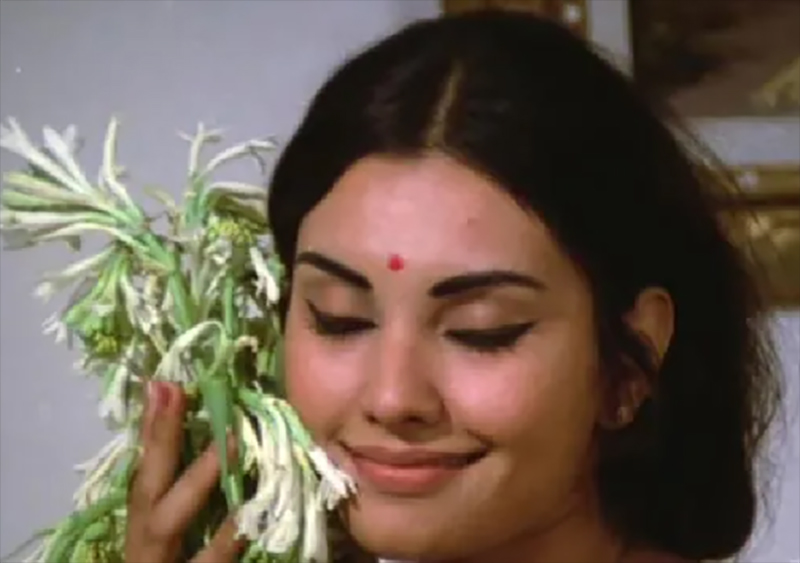

A scene from Chatterjee’s first film Sara Akash (1969)

A scene from Chatterjee’s first film Sara Akash (1969)

The importance of Basu Chatterjee lies in the kind of cinema he popularised when juxtaposed against the cinema that ruled the box office at the time.

The 1970s was the decade of the big blockbuster – Yaadon Ki Baaraat, Deewaar, Sholay, Amar Akbar Anthony. Yash Chopra and Ramesh Sippy, Nasir Hussain and Shakti Samanta were the dream merchants. Amitabh Bachchan and Dharmendra, Rishi Kapoor and Rajesh Khanna were the role models for the filmy hero, while Zeenat Aman and Hema Malini set a million young hearts aflutter. The aesthetic of Hindi cinema was larger-than-life.

They were not heroes and heroines, but the man and woman next door

Basu Chatterjee provided an alternative. His debut, Sara Akash, belonged firmly to the New Wave school of spare film-making. He however jettisoned this soon, opting for a middle road between this and the big-budget extravaganza.

Vidya Sinha in Rajnigandha

Vidya Sinha in Rajnigandha

In doing so he made ‘small’ beautiful and commercially viable. With Rajnigandha (1974), he revolutionised Hindi cinema, casting rank newcomers in a literary classic by Mannu Bhandari. The film, unlike any other film of the time (a runtime of approximately two hours, no lip-synched songs, no fights, no flashy clothes and make-up for its actors who looked nothing like Greek gods) broke all records at the box office.

He had already shown a penchant for a different approach to the cinema of the city in Piya Ka Ghar (1971), dealing with a couple finding their way to love and domesticity in the confined spaces of a one-room tenement in Mumbai shared by the extended family. While the latter starred Jaya Bhaduri (in one of her early roles) and Anil Dhawan (fresh from the FTII), Rajnigandha made stars of the unlikely duo of Amol Palekar and Vidya Sinha.

Over the next few films, Basu Chatterjee made his school of cinema an audience favourite. Chhoti Si Baat and Chitchor, both 1976, starred Amol Palekar, who soon came to be termed ‘the Amitabh Bachchan of middle-of-the-road cinema’. In Vidya Sinha, the director gave Hindi cinema the very antithesis of the ’70s heroine.

Piya Ka Ghar (1971) deals with a couple finding their way to love and domesticity in the confined spaces of a one-room tenement in Mumbai shared by the extended family.

Piya Ka Ghar (1971) deals with a couple finding their way to love and domesticity in the confined spaces of a one-room tenement in Mumbai shared by the extended family.

His characters epitomised the Everyman. They were not heroes and heroines, but the man and woman next door. The men were not macho style icons. They were often gentle, hesitant and even lacking in ambition. The women were down to earth and real, not coy and simpering.

And their world consisted of humble middle-class drawing rooms, local bus stops, double-decker Mumbai buses and trains, and office corners. Even when he cast superstars like Amitabh Bachchan (Manzil, inspired by Mrinal Sen’s Akash Kusum) and Dharmendra (Dillagi, with Hema Malini), the stars willingly shed their starry mannerisms to play everyday characters.

His spotlight was on literary classics, communities and women.

No one brought alive particular communities as lovingly as he did in his films like Khatta Meetha (the Parsis) and Baaton Baaton Mein (the Christians in Mumbai).

And few film-makers of the time were as adept at adapting literary classics as he was – Sara Akash (from a novel by Rajendra Yadav), Piya Ka Ghar (Vasant Kale, or Va Pu), Rajnigandha (based on a short story by Mannu Bhandari), Ratnadeep (Prabhat Mukhopadhyay), Swami and Apne Paraye (based on novels by Saratchandra Chattopadhyay) – giving his cinema a unique literary sensibility.

One of the most revolutionary aspects of his cinema lay in the woman his films portrayed. Right from Malti in Piya Ka Ghar, they were independent women with a mind of their own. They were determined, focused and unwilling to bow down to convention just because society demanded it.

Vidya Sinha’s Deepa in Rajnigandha is revolutionary in the way she is shown as unable to make up her mind about the two men she is dating. Zarina Wahab’s Geeta in Chitchor decides to follow her heart in the face of family opposition. In Swami, the woman reads Thomas Hardy and is torn between the man she thinks is her intellectual equal and her ‘simple’ husband. These women challenged the existing tropes on the portrayal of women in Hindi cinema.

And what all of us will be grateful to his films are the songs. ‘Yeh jeevan hai’ to ‘Kai baar yunhi dekha hai’ to ‘Rimjhim gire sawan’ , each song became timeless classic conveying tender feelings of love, life and myriad other emotions of aspirations and confusions that set our hearts aflutter.

Amitabh Bachchan and Moushumi Chatterjee set hearts aflutter in the famous rain song Rim Jhim Gire Sawan in the film Manzil

Amitabh Bachchan and Moushumi Chatterjee set hearts aflutter in the famous rain song Rim Jhim Gire Sawan in the film Manzil

This ability to carve out a different cinema was visible in the songs in his films as well. From ‘Yeh jeevan hai’ in Piya Ka Ghar to ‘Rajnigandha phool tumhare’ in Rajnigandha (‘Kai baar yunhi dekha hai’ from the same film won a National Award) to the evergreen songs of Chitchor to ‘Rimjhim gire sawan’ (arguably the finest rain song in Hindi cinema) in Manzil, the cinema of Basu Chatterjee provided Hindi cinema with some of its most loved and enduring classics.

A confused Vidya Sinha in Rajnigandha is torn between two men in her life

A confused Vidya Sinha in Rajnigandha is torn between two men in her life

The dream of 1969 proved short-lived. By the end of the 1970s, the cinema of the Basu Chatterjee-Hrishikesh Mukherjee-Gulzar School was shutting shop. Driven by a changing demographic, the onslaught of video piracy, some indifferent films by the film-makers themselves, and the advent of TV as a popular medium, kitschy commercial films were making a comeback in a big way and the next decades would witness a new low for Hindi films.

Amol Palekar and Ashok Kumar in Chhoti Si Baat

Amol Palekar and Ashok Kumar in Chhoti Si Baat

Basu Chatterjee, of course, led the first wave of top-notch and popular content in television with serials like Rajani, Byomkesh Bakshi, Darpan and Kakaji Kahin proving to be trailblazers. His legacy lives on in the cinema of every filmmaker who explores the life and world of the Everyman.

#BasuChatterjee, #Bollywood, #FilmandTelevisionInstituteofIndia