For nearly 190 years, scientists have searched for the origins of ancient sea-going reptiles from the Age of Dinosaurs. Now a team of Swedish and Norwegian paleontologists has discovered remains of the earliest known ichthyosaur(“fish-lizard”) on the remote Arctic island of Spitsbergen. A paper describing the team’s findings is published in Current Biology.

Ichthyosaurs are an extinct group of marine reptiles whose fossils have been recovered worldwide. They were among the first land living animals to adapt to life in the open sea, and evolved a fish-like body shape similar to modern whales. Ichthyosaurs were at the top of the food chain in the oceans while dinosaurs roamed the land, and dominated marine habitats for over 160 million years.

According to textbooks, reptiles first ventured into the open sea after the end-Permian mass extinction, which devastated marine ecosystems and paved the way for the dawn of the Age of Dinosaurs nearly 252 million years ago. As the story goes, land-based reptiles with walking legs invaded shallow coastal environments to take advantage marine predator niches that were left vacant by this cataclysmic event. Over time, these early amphibious reptiles became more efficient at swimming and eventually modified their limbs into flippers, developed a fish-like body shape, and started giving birth to live young; thus, severing their final tie with the land by not needing to come ashore to lay eggs.

The new fossils discovered on Spitsbergen are now revising this long accepted theory.

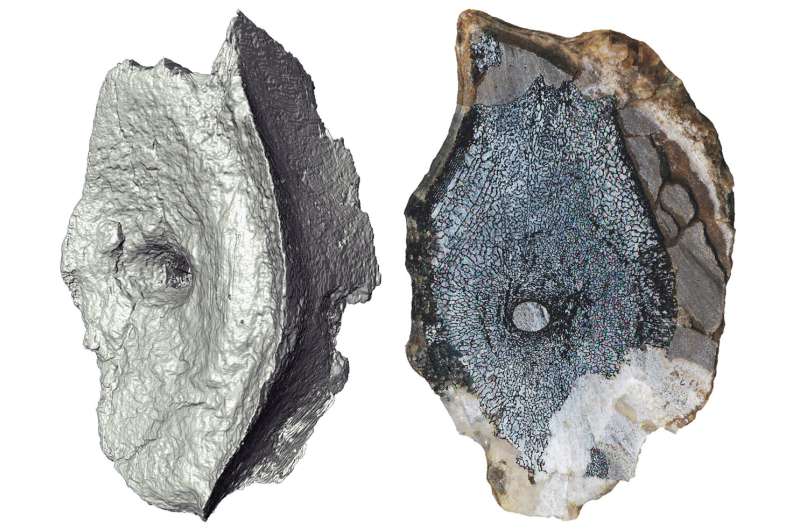

Close to the hunting cabins on the southern shore of Ice Fjord in western Spitsbergen, Flower’s valley cuts through snow-capped mountains, exposing rock layers that were once mud at the bottom of the sea around 250 million years ago. A fast-flowing river fed by snow melt has eroded away the mudstone to reveal rounded limestone boulders called concretions. These formed from limey sediments that settled around decomposing animal remains on the ancient seabed, subsequently preserving them in spectacular three-dimensional detail. Paleontologists today hunt for these concretions to examine the fossil traces of long-dead sea creatures.

During an expedition in 2014, a large number of concretions were collected from Flower’s valley and shipped back to the Natural History Museum at the University of Oslo for future study. Research conducted with The Museum of Evolution at Uppsala University has now identified bony fish and bizarre crocodile-like amphibian bones, together with 11 articulated tail vertebrae from an ichthyosaur.

Close to the hunting cabins on the southern shore of Ice Fjord in western Spitsbergen, Flower’s valley cuts through snow-capped mountains, exposing rock layers that were once mud at the bottom of the sea around 250 million years ago. A fast-flowing river fed by snow melt has eroded away the mudstone to reveal rounded limestone boulders called concretions. These formed from limey sediments that settled around decomposing animal remains on the ancient seabed, subsequently preserving them in spectacular three-dimensional detail. Paleontologists today hunt for these concretions to examine the fossil traces of long-dead sea creatures.

During an expedition in 2014, a large number of concretions were collected from Flower’s valley and shipped back to the Natural History Museum at the University of Oslo for future study. Research conducted with The Museum of Evolution at Uppsala University has now identified bony fish and bizarre crocodile-like amphibian bones, together with 11 articulated tail vertebrae from an ichthyosaur.

#OldestSeaReptile; #AgeOfDinosaurs; #ArcticIsland